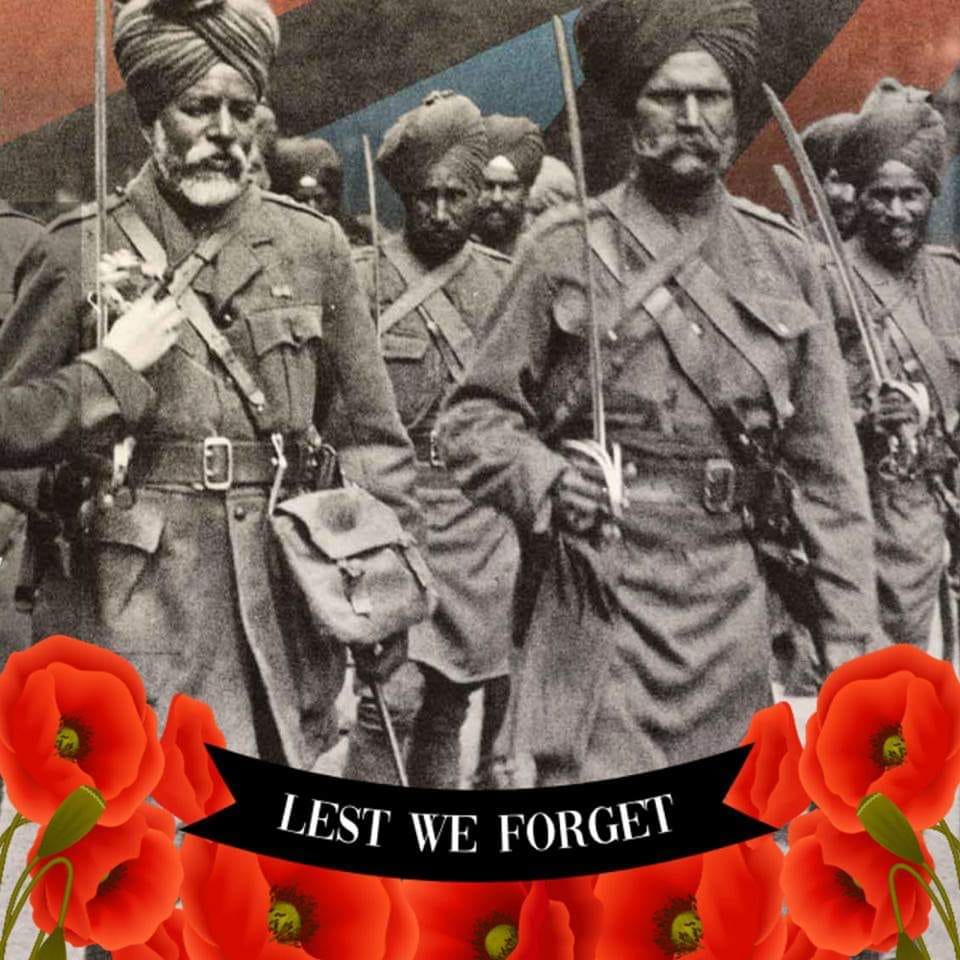

Documentary examining why followers of the Sikh religion were marked out as a ‘martial race’ under the British Empire, and how thousands of Sikh soldiers valiantly laid down their lives for Britain’s freedom across two world wars. With contributions from eminent historians, military experts and war veterans, the film features the last-ever interview with legendary WW2 Squadron Leader Mahinder Singh Pujji, and the first television broadcast of a rare audio recording of a WW1 Sikh prisoner of war, handed to Britain in 2010 after 94 years in German hands.

Bonus: Mangal Pandey

True story of Mangal Pandey, a sepoy of Indian origin fights against British rule and saves the life of his British commanding officer leading to a strong friendship between the two.

Bonus: Sardar Udham

True story of how a young Sardar Udham was left deeply scarred by the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. He escaped into the mountains of Afghanistan, reaching London in1933-34. There, Udham spent the most decisive 6 years of his life, re-igniting the revolution. On 13th March, 1940, 21yrs since carrying the unhealed wound, Udham Singh assassinated Michael O’Dwyer, the man at the helm of affairs in Punjab, April 1919.

Forgotten role of Indian soldiers who served in First World War marked at last‘Few people are aware 1.5 million Indians fought – that there were men in turbans in the same trenches as the Tommies’

A new book, For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front 1914-18 by Shrabani Basu, recounts for the first time some of the personal stories of the Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims from modern-day India and Pakistan who fought alongside the British and other allies in the conflict. For 12 months between 1914 and 1915, the British Indian Army fought on one of the bloodiest stretches of the Western Front. But despite contributing the largest volunteer army from Britain’s imperial dominions at a cost of some 70,000 lives, there is concern that the sacrifice of the fighters from pre-partition India has been allowed to slip between the cracks of the post-colonial history of both countries. Basu, a historian, told The Independent on Sunday: “Few people are aware that 1.5 million Indians fought alongside the British – that there were men in turbans in the same trenches as the Tommies … They have been largely forgotten, both by Britain and India. “The soldiers who had fought for their colonial masters were no longer worthy of commemoration in post-independence India. There is no equivalent of Anzac Day.

Amazon #ads

“The contribution of Indian and other Commonwealth soldiers should be part of the First World War curriculum in schools, and museums should highlight their stories. That is the only way to ensure that they do not become a footnote in history.” By Armistice Day, soldiers from the subcontinent had won 11 Victoria Crosses, including the very first awarded to a British Indian Army soldier – Khudadad Khan, a machine gunner with the 129th Baluchi regiment. The Germans were taken aback by the ferocity with which the Indians fought. One enemy soldier, who had witnessed Sikh troops in hand-to-hand combat at Neuve Chapelle in 1915, wrote: “At first we spoke of them with contempt. Today we look on them in a different light …. In no time they were in our trenches and truly these brown enemies are not to be despised. With butt ends, bayonets, swords and daggers we fought each other and we had bitter hard work.”

Often the Indian soldiers were forced to improvise, using jam tins packed with explosives as grenades and inventing the Bangalore torpedo – a tube filled with TNT used to blow holes in barbed wire. In order to sustain the Indian troops in the alien environment of northern France, a remarkable logistical operation was put in place, which included the setting up of separate kitchens to meet the dietary requirements of Muslims and Hindus. In many cases, cooking was carried out close to the front lines to allow curries to be supplied to the soldiers, at the cost of the lives of many orderlies killed by artillery as they ferried the hot food to the trenches. But the heavy death toll was also exacerbated by acts of negligence. The Indian regiments were sent to Europe in their tropical cotton drill; winter kit, including greatcoats, did not arrive before dozens had perished from cold and frostbite.

The racist attitudes of the era also enflamed tensions. Wounded Indian soldiers being cared for in hospitals in places such as Brighton were not allowed to receive direct care from English nurses, and recuperating troops were also kept under armed guard in locked camps. One injured private or “sepoy” felt sufficiently aggrieved to write a letter directly to King George V. “The Indians have given their lives for 11 rupees,” he wrote. “Any man who comes here wounded is returned thrice and four times to the trenches. Only that man goes to India who has lost an arm or a leg or an eye.” Eventually, Britain’s generals recognised that the Western Front was not the best place to deploy its Indian troops and instead sent them into battle in locations from Mesopotamia to Gallipoli, where they again fought valiantly.

In the 1920s a large memorial to India’s First World War dead was built in northern France at Neuve Chapelle, but until this month there has been little to mark their sacrifice on British soil. A memorial in honour of the 130,000 Sikh soldiers who fought in the conflict was unveiled a week ago at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, after a fundraising drive by British Sikhs. Organisers say they sensed a sea change in efforts to maintain the memory of the sacrifice of the soldiers of the Raj.

Jay Singh-Sohal, the founder of the charity behind the memorial, said: “In the immediate aftermath of the war there was a warmth to the Anglo-Indian relationship which was lost amid the atrocities committed by the British at the end of the colonial era. “Time has now healed some of those wounds and we can look with fresh eyes at the historic contribution of Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims. It is very important because it also helps British Asians to understand and feel part of Britain.” As Basu’s book makes clear, the men fighting in Flanders were under no illusions about the nature of the conflict into which they had been thrust. A poem by one Sikh soldier reads: “The cannon roar like thunder, the bullets fall like rain/ And only the hurt, the maimed and blind will ever see home again.”

Bonus: How Nolan forgot the desis at Dunkirk